In the days before June 5, Jordan had deployed in the West Bank opposite Israel ten of its eleven brigades, totaling some 45,000 men. In the north were three infantry brigades: one near the Jordan river, opposite the Israeli town of Beit Shean, one around the city of Jenin, and one near the city of Tulkarem (where Israel is only about 10 miles wide). In the central sector were four brigades: an infantry brigade near Qalqilya, right on the Israeli border, another near Latrun, also on the border, and two around Jerusalem. In the south was an infantry brigade around Hebron, and in the rear, near the Damia bridge over the Jordan river and near Jericho, were two armored brigades, the main striking forces of the Jordanian army.

The eleventh Jordanian brigade was deployed south of the Dead Sea, facing Israel’s Negev Desert and pointing towards the Egyptian forces in the Sinai. According to the joint Jordanian-Egyptian plans this brigade’s role was to fight into the Negev and link up with the advancing Egyptians, thereby cutting Israel in half.

An Iraqi brigade, based on the other side of the Damia Bridge, with three more on the way, and two Egyptian commando battalions deployed near Latrun rounded out the forces arrayed against Israel on the Jordanian front.

The western half of the of the West Bank — that is, the portion bordering on Israel — is mountainous and densely populated, especially the Old City of Jerusalem, and the large cities of Jenin, Nablus, Ramallah and Hebron. The terrain is nothing like the open spaces of the Sinai, so suited to tank warfare. In the West Bank the geography favored the defenders, offering innumerable ambush points and potential bottlenecks, which the Jordanians had supplemented by building many strategically located fortified positions, with trenches, bunkers, ammunition storerooms and gun emplacements.

However, because Egypt was the strongest and most threatening of the Arab countries, Israel had to deploy the bulk of its forces in the south. Consequently, against the eleven Jordanian brigades and the Iraqi expeditionary force, the Israelis could muster only three infantry brigades and an armored brigade.

Just after hostilities began between Israel and Egypt, the Egyptian commander Marshal Amer sent a message to Jordan’s King Hussein, reporting that 75 percent of Israel’s planes had been shot down or disabled, and urging Hussein to open a second front. As the King recounted in his book on the war:

It was now 9 A.M. on Monday, June 5, and we were at war.

Riad [the Egyptian general who commanded Jordanian forces] increased our fire power against the Israeli air bases by directing our heavy artillery – long-range 155’s – on the Israeli air force installations within our line of fire. Our field artillery also went into action, and our Hawker Hunters [British-supplied fighter jets] were ready to take part in the combined operation with the Iraqi and Syrians. (Hussein of Jordan: My “War” with Israel, by King Hussein, p 63)

With Jordanian artillery raining shells on Israeli targets from Jerusalem to Tel-Aviv and beyond, and Jordanian jets preparing to launch bombing runs, the King received through the U.N. a conciliatory message from Israel stating that if Jordan did not attack Israel, Israel would not attack Jordan. In the King’s own words:

… we received a telephone call at Air Force Headquarters from U.N. General Odd Bull. It was a little after 11 A.M.

The Norwegian General informed me that the Israeli Prime Minister had addressed an appeal to Jordan. Mr. Eshkol had summarily announced that the Israeli offensive had started that morning, Monday June 5, with operations directed against the United Arab Republic, and then he added: “If you don’t intervene, you will suffer no consequences.”

By that time we were already fighting in Jerusalem and our planes had just taken off to bomb Israeli airbases. So I answered Odd Bull:

“They started the battle. Well they are receiving our reply by air.”

Three times our Hawker Hunters attacked the bases at Natanya in Israel without a loss. And our pilots reported that they destroyed four enemy planes on the ground, the only ones they had seen.

On their side, the Iraqis bombed the airport at Lydda. And a little later, the Syrians finally headed for the base at Ramad David and the refineries in Haifa. (Hussein, p. 64-65)

Despite the Jordanian attacks, the Israelis did not respond. As the Israeli Foreign Minister Abba Eban put it, the Israelis hoped that “King Hussein was making a formal gesture of solidarity with Egypt,” in other words, that the artillery barrage and bombing runs were for show, and that they did not presage a general offensive. But this was not to be – after the Israelis sent their peace message, the Jordanian attacks only grew in intensity.

This may be because the King received a second message from Egypt’s Marshal Amer, which stated that:

.. the Egyptians had put 75 percent of the Israeli air force out of action! The same message said that U.A.R. [i.e. Egyptian] bombers had destroyed the Israeli bases in a counterattack, and that the ground forces of the Egyptian army had penetrated into Israel by way of the Negev!

… when a little later, our radar screens showed planes flying from Egypt to Israel, we didn’t give it a thought. We simply assumed they were from the U.A.R. air force on their way to a mission over Israel. (Hussein, p 66)

The First Israeli Response

Along with these aerial attacks Jordanian troops also crossed the armistice lines and took Government House, the UN headquarters on the Biblical “Hill of Evil Counsel” in the no-man’s land between the two countries, directly threatening Israeli positions in southern Jerusalem, and finally provoking a counterattack. Again, quoting King Hussein:

At 12:30 on that 5th of June came the first Israeli response to the combined bombing by the Jordanians, Iraqis and Syrians. (Hussein, p 68)

When it became clear to Israeli leaders that war with Jordan was unavoidable, they scrambled to add forces to the theater, drawing from the north a division under Major General Elad Peled, and from the south a paratroop brigade under Colonel Motta Gur, which was originally intended to go into action near El Arish. But first the Israeli air force was ordered to respond to the Jordanian air attacks, which it did with despatch. Catching the King’s planes refueling at their bases in Mafraq and Amman, the Israeli jets wrought havoc – all 22 of Jordan’s Hawker Hunter jets were destroyed, as were the air bases, which meant that Jordan no longer had an air force. The attacks from the Syrian and Iraqi air forces brought Israeli retaliation as well, with much of the Syrian air force wiped out, and the Iraqi base whose planes had attacked Israel also devastated.

As in the Sinai fighting, the Israeli General Staff took into account that U.N. or great power intervention might impose a cease-fire, so they planned a two phase campaign, the first phase covering the minimal objectives they wanted to achieve. These objectives were three: (1) To eliminate the bulge into Israeli territory in the north, near Jenin, and thereby remove from artillery range the Israeli air base at Ramat David and the Jezreel Valley; (2) To eliminate the Latrun bulge which had always threatened Israeli communications with Jerusalem. (Many Israeli soldiers had been killed in the 1948 War during at least four unsuccessful attacks on the Latrun strongpoints, and as a young soldier Ariel Sharon was gravely wounded there.); (3) To open a secure road to the Mount Scopus enclave, a patch of Israeli-held territory in Jerusalem that since 1948 had been surrounded by Jordan (and resupplied only by periodic U.N. supervised convoys).

Once these objectives were attained, were the fighting to continue Israel would be poised to take the key roads through and along the north-south mountain range that divides the West Bank, and control of those roads meant capture or destruction of the bulk of Jordan’s army.

In accord with the first phase of their plans, the Israeli counterattack began by ejecting the Jordanian soldiers who had stormed Government House. Major General Uzi Narkis, chief of Israel’s Central Command, gave the job to the 16th Jerusalem Brigade, and at 2:30 in the afternoon the brigade, all reservists, began their assault. Two infantry companies joined by six Sherman tanks crossed the 1948 armistice lines and approached the position. After a brief but sharp battle Government House fell to the Israelis, who then wheeled around to the south to attack the village of Sur Baher, which finally fell the next morning, giving the Israelis control of the road from Jerusalem to Bethlehem and Hebron. The Jordanian forces to the south, in the hilly region around Hebron, were now cut off.

At the same time, in the northern sector of Jerusalem, General Narkis sent the armored Harel Division from the Latrun area down the road towards Jerusalem. Before reaching the city limits the division, under the command of Col. Uri Ben-Ari, turned off the road to the northeast and launched three separate attacks into Jordanian-held territory, the objective being the key Ramallah ridge. Taking the ridge would give Israel control of the northern and eastern approaches to Jerusalem, along with the main road through the West Bank from Jericho, and would isolate Jerusalem from the rest of the West Bank. Down through the ages every force that would control Jerusalem has had to fight for this ridge, from the Biblical Joshua, to the British under General Allenby during the First World War

The Jordanian army, known as the Arab Legion, had been well-trained by the British for decades – indeed, until 1956 it had been led by a British officer, General Sir John Bagot Glubb. The professional soldiers leading the Arab Legion therefore made sure that the ridge was extremely well defended.

The attacking Israelis were without a flail tank to clear a route through the first Jordanian obstacle, a deep minefield, so Israeli sappers had to clear a path by hand. This accomplished at some cost, Ben-Ari’s tanks, often firing at point-blank range, then took in succession Jordanian strong points near Radar Hill, Sheikh Abed El-Aziz, and Beit Iksa. Moving further up the ridge, the Israelis then enveloped and conquered the fortified village of Biddu, at which point Ben-Ari’s tanks swung east onto the main road and headed for Nebi Samuel (burial place of the Prophet Samuel).

Parallel with this operation an Israeli brigade under Col. Moshe Yotvat defeated the Jordanian and Egyptian forces at the Latrun police fortress, putting that key strategic point in Israeli hands as well.

With Jordanian forces around Jerusalem falling back under Israeli tank and infantry assaults, General Ata Ali, commander of the Jordanian 27th Brigade, pleaded for help from King Hussein, who agreed to send reinforcements. Traveling under cover of darkness, elements of the Jordanian 60th Armored Brigade, accompanied by an infantry battalion, began to make its way towards Jerusalem along the Jericho road. They were spotted, however, by the Israeli air force, which, after dropping illumination flares, strafed and bombed the Jordanian column, wiping it out. Other Jordanian attempts to bring reinforcements to Jerusalem were also beaten back, either by armored ambushes or air assaults.

Thus, after the first day of fighting, with control of the roads and the air, the Israelis had succeeded in isolating Jerusalem, and now there were two large tasks before them – breaking into and taking the Jordanian-held part of the city, including the Old City, location of the Temple Mount, the holiest site in Judaism, and clearing the bulk of the Jordanian army from the rest of the West Bank.

The Battle for Jerusalem

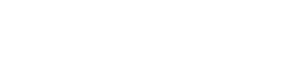

On the night of June 5, with control of the approaches to Jerusalem, the Israelis began their assault on the city itself. To the north of the city searchlights illuminated Jordanian strong points, and artillery and mortar batteries zeroed in, hitting one after the other. Just after 2 in the morning on June 6, a combined force of Gur’s paratroopers and the Jerusalem Brigade’s tanks and reconnaissance unit crossed no-man’s land near the Mandelbaum Gate (a crossing point between the two Jerusalems since 1948). The heavily-fortified Police School fell to one of Gur’s battalions, which then moved up to attack the even more heavily-fortified Ammunition Hill, where a legendary battle ensued. The combat, often hand to hand in trenches and bunkers, went on for four bloody hours, as both sides fought with great courage.

Finally though, the Jordanian defenders were beaten, and Ammunition Hill fell to the Israelis. By mid-morning on June 6 the battalion had driven further east and linked up with the Israeli Mount Scopus enclave.

Meanwhile Gur’s other battalions, fighting in the same general area, subdued the Jordanian positions around the so-called American Colony and converged on the Rockefeller Museum, near the northern edge of the walled Old City. Despite their location right up against the walls of the Old City, Gur’s paratroopers were not yet able to conquer the city, because Jordanian forces still held the Augusta Victoria Hill, high ground overlooking the city from the east.

At 8:30 in the morning on June 7 the paratroopers therefore launched a three-pronged assault – one battalion attacked August Victoria Hill from Israeli-held Mount Scopus, another battalion attacked August Victoria by climbing up the valley between it and the Old City, and a third battalion, led by Gur himself drove around the Old City walls to break into the city via St. Stephen’s Gate. Arriving at the gate, Gur’s halftrack plowed through and into the Old City. Gur’s two other battalions, their missions compete, followed him in, where they found little resistance. Gur himself made for the holiest site in Judaism, the Temple Mount, where the biblical Jewish temples stood. When he got there he famously radioed to his commanders, “The Temple Mount is in our hands.”

The Battles Outside Jerusalem

Outside of Jerusalem the main battles for the West Bank, known to Israelis as Judea and Samaria, were centered in the areas of Jenin and Nablus, in the north of the territory. A primary target in the Jenin fighting was Jordanian artillery that was shelling the Israeli airbase at Ramat David. While in all of these battles Jordanian armor acquitted itself very well, in the end the well-trained and led Arab Legion could not cope with the joint air and armor attacks of the Israelis.

By 8 PM on June 7 both sides had accepted a UN cease fire ending the fighting on the West Bank, leaving Israel in complete control of the territory.

General references

- Israel: The Embattled Ally, Nadav Safran, Harvard University Press

- Hussein of Jordan: My War With Israel, King Hussein, Peter Owen Limited

- Warrior: An Autobiography, Ariel Sharon, Simon and Shuster

- The Arab-Israeli Wars, Chaim Herzog, Random House

- Arab-Israeli Wars, A.J. Barker, Hippocrene Books

- Chariots of the Desert, David Eshel, Brassey’s

- The Six Day War, Israel Defense Forces Website